The Micro-Frontend Revolution: Why Monolithic SPAs Are Dead in 2025 (Complete Migration Guide)

📧 Subscribe to JavaScript Insights

Get the latest JavaScript tutorials, career tips, and industry insights delivered to your inbox weekly.

Three years ago, I joined a company with a React SPA that took eight minutes to build. Eight minutes. Every single code change, no matter how trivial, required waiting nearly ten minutes before you could see if your fix actually worked. The production bundle was 6.2MB gzipped. Initial page load on a fast connection took four seconds. On 3G? Users waited almost a minute staring at a loading spinner.

The application had started innocently enough five years earlier. A small team built a clean, modern SPA using create-react-app and React Router. It worked beautifully. Fast forward to my arrival, and that same application now had 47 developers across four continents all committing to the same repository. The codebase exceeded 280,000 lines of code. Every deployment was a Russian roulette game of "will this break something unexpected in a completely different part of the app?"

This is the story of almost every successful SPA. They start small and elegant. They grow into unmaintainable monsters that consume developer productivity and degrade user experience. And in 2025, there's finally a proven solution that doesn't require rewriting everything from scratch.

The Monolithic SPA Death Spiral

Let me paint you a picture of what happens when SPAs scale. It's not pretty, and if you're working on a large application right now, you're probably living this nightmare.

You start with a reasonable architecture. Components are organized logically. State management makes sense. The build takes 30 seconds. Life is good. Then the business succeeds. More features get added. More developers join. More teams form. Suddenly you have six teams all working in the same codebase, and the problems multiply.

Team A updates a shared component because they need a new prop. They test their feature thoroughly. Everything works. They deploy on Friday afternoon. Monday morning, Team B discovers their checkout flow is completely broken because it depended on that component's previous behavior. Nobody noticed because the component was used in 47 different places across the application, and comprehensive testing would have required running every single user flow.

The build time creeps up. First to two minutes. Then five. Eventually eight. Developers start taking coffee breaks during builds. Some start working on two features simultaneously, context-switching between tasks while waiting for builds to complete. Productivity plummets, but the metrics never capture this invisible cost.

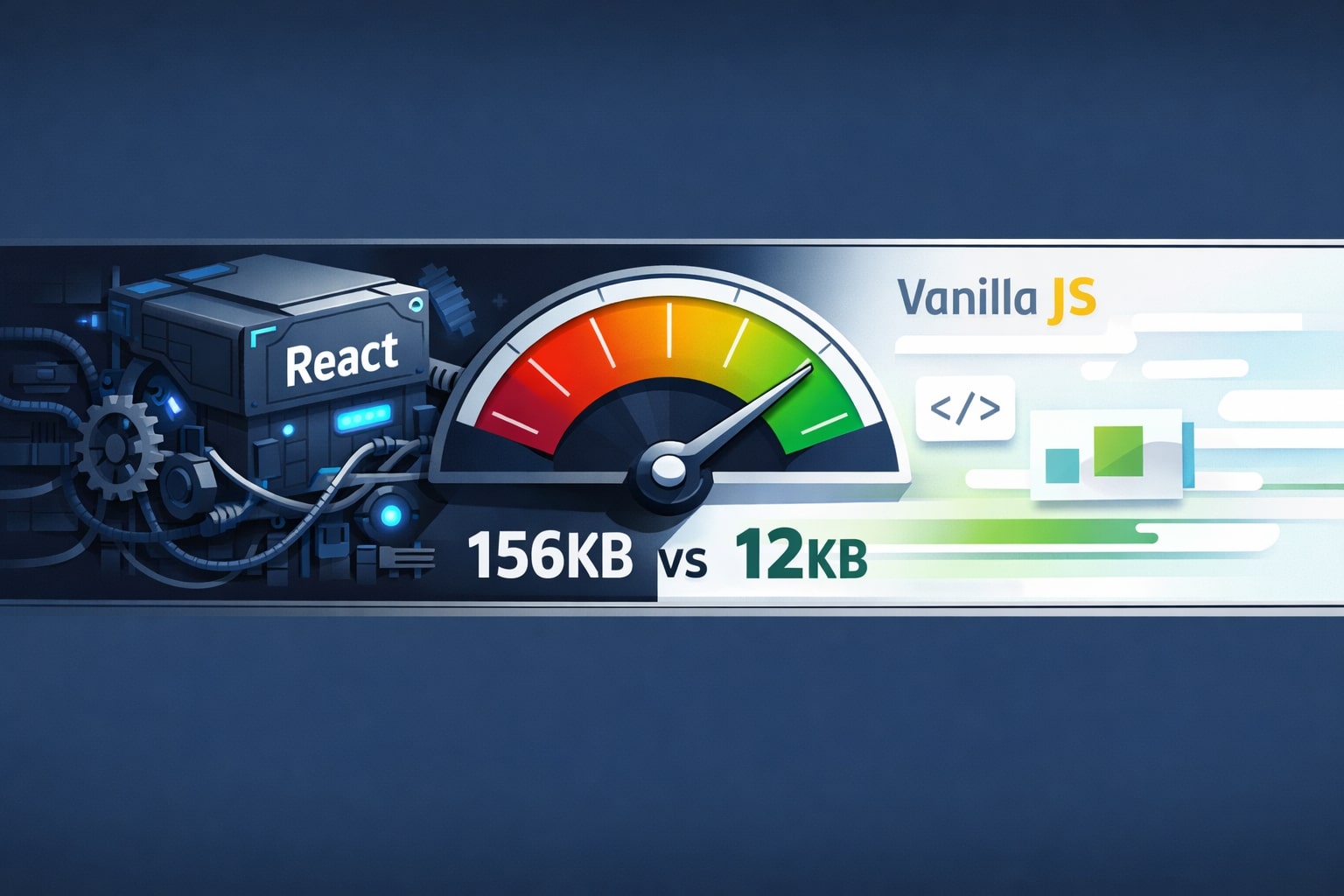

The bundle size grows relentlessly. You implement code splitting, but it only delays the inevitable. The initial chunk still needs the entire routing configuration. It needs the authentication logic. It needs the layout components. It needs all the third-party libraries that everything depends on. You're shipping 2MB of JavaScript just to render a login form.

Testing becomes a full-time job. Your test suite runs for 35 minutes in CI. Developers stop running tests locally because it's too slow. The feedback loop extends from minutes to hours. You catch bugs in code review instead of during development. Sometimes you catch them in production.

Deployments terrify everyone. You can't deploy just the feature you built. You must deploy the entire application. That means coordinating with every team to ensure their code is ready. It means extensive regression testing because any change could affect anything. Large companies I've worked with deploy their SPAs once per week, maximum, because the coordination overhead is too high.

The worst part? New developers take months to become productive. The application is too large to understand. There's no clear separation between features. Everything depends on everything else. Senior developers spend more time helping juniors navigate the codebase than actually building features.

This isn't a horror story. This is reality for most companies that built SPAs three to five years ago. The architecture that made sense for a small team building a focused application becomes a straightjacket when that application succeeds and grows.

What Micro-Frontends Actually Are

Micro-frontends apply the proven principles of microservices to frontend development. Instead of one massive application, you build multiple smaller applications that work together seamlessly. Each application can be developed, tested, and deployed independently while combining to form a cohesive user experience.

The core idea is simple. Split your application by business domains or features. Your e-commerce site has a product catalog team, a checkout team, and a user account team. Each team owns their entire stack from frontend to backend. They deploy independently. They choose their own technology. They move at their own pace.

When a user visits your site, they don't see three separate applications. They see one unified experience. The product listing integrates seamlessly with the shopping cart. The checkout flow feels like part of the same application. But behind the scenes, these are distinct codebases managed by different teams with different release cycles.

This architectural shift solves the fundamental problems that kill monolithic SPAs. Build times shrink because each team only builds their own code. Bundle sizes decrease because users only download the code they need for the current page. Testing becomes manageable because each micro-frontend has a focused scope. Deployments happen continuously because teams don't need to coordinate.

The mental model is different too. In a monolith, you think in terms of components and features scattered across a giant codebase. With micro-frontends, you think in terms of complete vertical slices of functionality. The checkout team owns everything checkout related from the database schema to the button styling. This ownership creates accountability and enables genuine autonomy.

Companies that have made this transition report dramatic improvements. Spotify reported a 4x reduction in deployment time and 2x increase in developer velocity. IKEA reduced their time to market for new features from months to weeks. Zalando enabled their teams to deploy independently without coordination, moving from monthly releases to daily deployments.

These aren't theoretical benefits. They're measured improvements in real production systems serving millions of users. The micro-frontend architecture works, and it works at scale. But the transition isn't trivial, and the implementation details matter enormously.

Module Federation Changes Everything

Before 2020, implementing micro-frontends was painful. You had options like iframes, which provided isolation but terrible performance and awful user experience. You could use single-spa, which worked but added significant complexity and required careful coordination. You could build-time compose your applications, but that defeated the purpose of independent deployments.

Then Webpack 5 introduced Module Federation, and everything changed. Suddenly you could dynamically load code from one application into another at runtime with minimal configuration. The applications could share dependencies intelligently to avoid duplication. The developer experience improved dramatically.

Module Federation works through a deceptively simple concept. Each micro-frontend exposes certain modules through a manifest file. Other applications can consume those modules dynamically at runtime. Webpack handles all the complexity of loading the code, resolving dependencies, and ensuring nothing breaks.

Here's what makes it powerful. Imagine your header component lives in one application and your product list lives in another. With Module Federation, your main application can import both dynamically. If they both use React, Webpack ensures React is only loaded once and shared between them. If one uses React 18 and another uses React 17, Webpack handles that too, loading both versions but keeping them isolated.

The technical implementation relies on JavaScript module loading at runtime. Each micro-frontend generates a special entry file called remoteEntry.js. This file contains metadata about what modules the application exposes and what dependencies it needs. The host application loads this entry file, parses the metadata, and dynamically imports the exposed modules.

The beauty is that this happens transparently. From your code's perspective, you're just importing a component like any other. The complexity of loading it from a different application, resolving shared dependencies, and managing versioning all happens invisibly at the module loading layer.

Performance is better than you'd expect. The initial overhead of loading the remoteEntry.js file is minimal, typically under 10KB. Once loaded, the modules are cached aggressively by the browser. Shared dependencies mean you're often downloading less code than in a traditional SPA where everything is bundled together.

The development experience is equally impressive. You can run your micro-frontend in isolation during development, testing it independently without needing the entire application. You can point it at production versions of other micro-frontends to test integration. You can even load different versions of micro-frontends dynamically for A/B testing or gradual rollouts.

Companies like ByteDance, which owns TikTok, built their entire web platform using Module Federation. Their application loads different features dynamically based on the user's location, device, and feature flags. They deploy new features continuously without coordinating across teams. The architecture scales to hundreds of developers working simultaneously without stepping on each other's toes.

The Real-World Tradeoffs Nobody Tells You

Micro-frontends aren't free. The architecture introduces complexity that monolithic applications don't have. Understanding these tradeoffs before you commit is crucial because some of them are deal-breakers for certain projects.

Shared state becomes significantly more complicated. In a monolith, you have a single Redux store or Context provider. Components anywhere can access any state. With micro-frontends, each application has its own state management. Sharing state across applications requires explicit communication through events, shared state libraries, or query parameters. This friction is intentional to enforce boundaries, but it makes some patterns that were easy in monoliths much harder.

You also introduce runtime complexity. Monolithic SPAs have predictable behavior because everything is bundled together at build time. With Module Federation, you're loading code dynamically at runtime. If a remote module fails to load because of a network error or deployment issue, you need fallback strategies. Your application needs to gracefully handle scenarios where parts of it aren't available.

The build and deployment pipeline becomes more sophisticated. Instead of one build process, you have multiple. Each micro-frontend needs its own CI/CD pipeline. You need orchestration to ensure compatible versions work together. You need monitoring to detect when one micro-frontend deploys a breaking change that affects others. The infrastructure complexity is real.

Testing changes too. You can no longer run a single test suite that covers everything. Each micro-frontend tests its own functionality in isolation, which is faster and more focused. But integration testing becomes harder because you need to test how multiple micro-frontends work together. You need contract testing to ensure interfaces remain compatible when teams deploy independently.

Performance requires careful attention. While Module Federation enables code sharing, you can easily end up downloading more code than necessary if you're not thoughtful about boundaries. Loading many small modules can be slower than loading one optimized bundle. You need to design your micro-frontends at the right granularity and implement proper caching strategies.

The learning curve for developers is steeper. Junior developers who are used to monolithic applications will struggle initially with the distributed nature of micro-frontends. They need to understand module loading, asynchronous imports, error boundaries, and cross-application communication patterns. The path to becoming productive takes longer, though the long-term benefits outweigh this initial cost.

Organizational complexity increases too. You need clear ownership boundaries. You need team agreements about shared dependencies and communication patterns. You need architectural governance to prevent teams from creating incompatible designs. Micro-frontends work best when your organization is structured around product verticals rather than technical layers.

When You Actually Need Micro-Frontends

Let me be direct. Most applications don't need micro-frontends. If you're a small team building a focused application, a well-structured monolithic SPA will serve you better. The complexity of micro-frontends only pays off at certain scales.

You need micro-frontends when you have multiple teams working on the same application. The number that matters is roughly six developers. Below that threshold, coordination overhead is low enough that everyone can work in the same codebase effectively. Above that threshold, coordination costs start dominating development time, and splitting the application becomes worthwhile.

You need micro-frontends when your application has distinct business domains that naturally separate. An e-commerce platform with product catalog, checkout, user accounts, and customer service naturally splits into four micro-frontends. A B2B SaaS tool with marketing site, application shell, and multiple feature modules works well. A simple blog or portfolio site definitely doesn't need this complexity.

You need micro-frontends when independent deployment is critical to your business. If you're shipping features multiple times per day and coordination is blocking deployments, micro-frontends enable genuine continuous deployment. Each team ships when they're ready without waiting for others. But if you're deploying weekly or monthly anyway, the independent deployment benefit doesn't matter as much.

You need micro-frontends when different parts of your application have drastically different requirements. Maybe your main application uses React but your data visualization team wants to use D3 without framework overhead. Maybe most of your app is standard but one feature needs WebAssembly for performance. Micro-frontends enable this technology diversity without forcing everything into one stack.

You don't need micro-frontends if build time and bundle size aren't problems. If your application builds in under two minutes and the production bundle is under 500KB, you're fine. The performance and velocity benefits of micro-frontends won't offset the complexity cost. Wait until you actually feel pain before adding this architectural complexity.

You don't need micro-frontends if your team lacks DevOps maturity. The deployment pipeline complexity is significant. If setting up CI/CD for one application is challenging for your team, don't try to manage multiple pipelines until you've built that competency. Start simpler and evolve later.

You don't need micro-frontends if your application doesn't have natural boundaries. Forcing artificial splits in a cohesive application creates more problems than it solves. If every feature touches every other feature and state sharing is extensive, micro-frontends will make your life miserable. The architecture works when boundaries are clean, not when everything is tightly coupled.

The honest truth is that probably 80% of applications don't need micro-frontends. They're solving problems that smaller, focused applications don't have. But for the 20% that do need them, particularly large enterprise applications with multiple teams, the benefits are transformative. Knowing which category your application falls into is critical before you commit to this architecture.

The Step-by-Step Migration Strategy

Migrating an existing monolithic SPA to micro-frontends without destroying your product requires a deliberate, incremental approach. I've done this migration three times now at different companies. Here's the proven strategy that works.

Start by identifying natural boundaries in your application. Look for features or pages that are relatively self-contained and don't share much state with the rest of the application. Common candidates include user settings, help documentation, admin dashboards, or specific feature modules that one team owns. These become your first micro-frontends.

Don't attempt a big-bang rewrite. That's how projects fail. Instead, implement the strangler fig pattern. Build new micro-frontends alongside your existing monolith. Route specific URLs to the new micro-frontends while everything else still runs in the monolith. Users see no difference, but you're gradually replacing the old system with new architecture.

The technical implementation starts with setting up your first micro-frontend. Create a new application using Vite or Next.js or whatever meta-framework makes sense for your stack. Configure Module Federation to expose the components you want to share. Deploy this application independently to its own URL.

Update your monolith to act as the host application. Configure Module Federation to load the remote micro-frontend. Create a dynamic import that loads the remote component when needed. Implement error boundaries to gracefully handle loading failures. Update your routing to direct specific paths to the micro-frontend instead of the monolith's components.

Shared dependencies need careful management. React, date libraries, utility libraries should be marked as shared in both the host and remote configurations. This ensures they're only downloaded once. But be specific about versions. Webpack can handle loading multiple versions if needed, but it's better to align on compatible versions across all micro-frontends.

State management requires rethinking. Each micro-frontend manages its own local state. For global state like authentication or user preferences, create a shared state library that all micro-frontends can import. Use events or pub/sub patterns for communication between micro-frontends when necessary. Keep these communication channels minimal and well-defined.

Styling coordination matters more than you'd think. You need a design system that all micro-frontends follow. Component libraries, CSS variables, and utility classes should be shared. But each micro-frontend should be able to bundle its own styles independently. CSS-in-JS solutions like styled-components or Tailwind CSS work well for this because styles are scoped by default.

Your deployment pipeline changes fundamentally. Each micro-frontend gets its own repository and CI/CD pipeline. When code merges to main, it triggers a build, runs tests, and deploys automatically. The deployment doesn't require coordination with other teams. But you need version management to track which versions of micro-frontends are deployed together in each environment.

Testing requires a new approach. Each micro-frontend has its own test suite covering its functionality. These run independently and quickly. For integration testing, create contract tests that verify the interfaces between micro-frontends remain stable. Use tools like Pact or write custom contract tests. Don't try to run the entire application in your test suite.

Monitoring becomes more important and more complex. You need to track which micro-frontends are loaded, how long they take to load, and when loading fails. Implement distributed tracing so you can follow requests across micro-frontend boundaries. Set up alerts for when micro-frontends fail to load or take too long.

The rollout strategy matters enormously. Start with one low-risk feature. Maybe user settings or a help section. Get that working smoothly with monitoring and proper error handling. Learn from the experience. Then tackle a more complex feature. Gradually extract functionality from the monolith until it becomes just the shell that loads other micro-frontends.

This migration took us 18 months at my last company. We started with the admin dashboard, which was perfect because it was self-contained and used by internal users who were forgiving of issues. We extracted the user profile next, then the analytics dashboard, then the main product catalog. By the end, the original monolith was just the authentication shell and routing orchestration. Everything else lived in independent micro-frontends.

Building Micro-Frontends From Scratch

If you're starting a new project, you have the luxury of doing micro-frontends right from the beginning. The decisions you make now will determine whether this architecture thrives or becomes a maintenance nightmare.

Start with a clear domain model. Before writing any code, map out the business domains in your application. E-commerce might have catalog, cart, checkout, and account management. B2B SaaS might have dashboard, analytics, settings, and admin. Each domain becomes a potential micro-frontend. The key is ensuring these domains are relatively independent with minimal cross-domain data flow.

Choose your technology stack deliberately. All micro-frontends should use compatible technologies, even if not identical. If one uses React 18 and another React 19, Module Federation handles it but you're increasing complexity. Better to standardize on React 18 across everything until you're ready to upgrade all at once. Same principle applies to TypeScript versions, build tools, and major dependencies.

Establish architectural standards early. Create guidelines for how micro-frontends communicate, how they handle errors, how they manage shared state, and how they style components. These standards prevent each team from solving the same problems differently, which leads to inconsistent user experience and integration headaches.

Your shared design system is critical. Build this first before individual micro-frontends. Create a component library with buttons, inputs, modals, and common UI patterns. All micro-frontends import from this shared library. When you update the design system, all micro-frontends automatically get the updates. This ensures consistency across your application.

Authentication and authorization deserves special attention. These typically live in a shared authentication service that all micro-frontends use. Implement token-based authentication with refresh logic in a shared library. Each micro-frontend imports this library and doesn't reimplement authentication. When security updates are needed, you update one library and all micro-frontends get the fix.

Routing coordination requires planning. Decide which micro-frontend owns which URL patterns. The checkout micro-frontend owns everything under /checkout. The account micro-frontend owns /account and /settings. Document these ownership boundaries clearly. Implement routing at the shell level that directs URLs to the appropriate micro-frontend.

Database architecture follows the same domain boundaries. Each micro-frontend's backend services own their data. If the checkout service needs user data, it calls the user service's API rather than accessing the user database directly. This separation prevents coupling at the database level, which would defeat the purpose of independent deployment.

Development workflow needs careful setup. Developers should be able to run their micro-frontend locally while loading deployed versions of other micro-frontends. Configure Module Federation to point at production or staging URLs for remotes during local development. This way, you test integration without running everything locally.

CI/CD pipeline infrastructure is your foundation. Each micro-frontend repository has its own pipeline. Push to main triggers build, test, and deploy automatically. The deploy updates a registry or import map that tells the shell application where to find the latest version. Rollbacks involve updating that registry to point at the previous version.

The Technology Landscape in 2025

The micro-frontend ecosystem has matured significantly. Multiple proven approaches exist, each with different tradeoffs appropriate for different scenarios.

Module Federation remains the most popular choice for new projects. Webpack 5 introduced it, but now Vite through @originjs/vite-plugin-federation and Rspack both support it. The approach is standardized enough that you're not locked into a specific build tool. The mental model of remotes, hosts, and shared dependencies works well and the tooling is mature.

Web Components offer an alternative approach that's framework agnostic. You can build micro-frontends in React, Vue, Svelte, or vanilla JavaScript and compose them using custom elements. The isolation is stronger than Module Federation, which helps prevent conflicts. But the developer experience is rougher and performance can suffer from the abstraction layer.

Single-SPA was the original micro-frontend framework and it's still relevant in 2025. It provides more structure and conventions than raw Module Federation. If you want opinionated patterns for routing, lifecycle management, and application orchestration, single-SPA delivers. The tradeoff is more framework lock-in and less flexibility than Module Federation.

Server-side composition is gaining traction. Instead of composing micro-frontends in the browser, you compose them on the server and stream the result. Edge computing platforms like Cloudflare Workers and Vercel Edge make this practical. The benefit is faster initial page loads and better SEO. The downside is more complex infrastructure and less dynamic behavior.

Import maps are the future standard for module loading in browsers. They're already supported in all modern browsers without polyfills. Combined with ES modules, they provide a standardized way to do what Module Federation does with less tooling dependency. The ecosystem is still catching up, but this is where micro-frontends are heading long-term.

Monorepo tools like Nx and Turborepo make managing multiple micro-frontends significantly easier. They provide fast builds through caching, coordinate versioning across packages, and make it feasible to keep all micro-frontends in one repository while still deploying them independently. Most large companies doing micro-frontends seriously are using these tools.

Real Companies, Real Results

The proof is in production systems serving real users. Let's look at concrete examples of companies that made this transition successfully.

Spotify rebuilt their entire web player using micro-frontends. Different teams own different features like the music player, playlist management, search, and recommendations. They deploy their features independently dozens of times per day. The migration took two years but reduced their deployment cycle time by 75% and improved developer velocity dramatically.

IKEA's retail website serves millions of customers globally. They migrated from a monolithic frontend to micro-frontends organized around shopping journeys. Product browsing, cart management, checkout, and account management are all separate micro-frontends. Different teams work in parallel without blocking each other. Their time to market for new features dropped from months to weeks.

Zalando operates one of Europe's largest e-commerce platforms. They documented their micro-frontend architecture publicly, showing how different teams manage separate product categories using their preferred frameworks and tools. The architecture enabled them to scale to dozens of teams without coordination overhead. Each team ships when they're ready.

American Express pioneered micro-frontends in financial services starting in 2016. Their customer-facing applications use this architecture to enable rapid feature development while maintaining security and compliance. They've spoken publicly about how micro-frontends solved their scaling issues and accelerated development cycles.

These aren't small companies experimenting with new ideas. These are massive organizations with millions of users, strict performance requirements, and complex business logic. The fact that they all converged on micro-frontends independently validates that this architecture solves real problems at scale.

The common thread in these success stories is organizational maturity. These companies had the infrastructure, tooling, and processes to support the additional complexity. They had clear product ownership boundaries. They had DevOps expertise. They didn't adopt micro-frontends because they were trendy. They adopted them because monolithic frontends were actively preventing them from executing their business strategy.

The Migration Timeline: What to Expect

Setting realistic expectations matters. Migrating to micro-frontends is a multi-month or multi-year journey depending on your application's size and complexity.

Month one involves planning and proof of concept. Identify the first feature to extract. Set up the infrastructure for Module Federation. Build a simple micro-frontend and get it deployed. Integrate it into your monolith. This phase should produce something running in production, even if it's just a single page.

Months two through four focus on extracting your second and third micro-frontends. These should be progressively more complex features that test your architecture decisions. By month four, you should have proven that the approach works and identified any infrastructure gaps. You should also have established patterns that other teams can follow.

Months five through twelve involve accelerating extraction. At this point, multiple teams can work in parallel extracting different features. The pace picks up significantly because you've solved the hard infrastructure problems and established clear patterns. Most of the original monolith gets extracted during this phase.

Year two is about refinement and completion. You're dealing with the remaining complex, tightly coupled parts of the monolith that are hardest to extract. You're improving performance, consolidating shared libraries, and making the developer experience smooth. The monolith shrinks to just the shell that orchestrates everything else.

This timeline assumes a moderately complex SPA with several teams working on it. Smaller applications might complete faster. Truly massive applications might take longer. The key is maintaining velocity while not breaking production. Incremental progress beats perfect architecture.

Your Decision Point

You're at a crossroads. You can continue with your monolithic SPA, accepting the limitations and working around them. Or you can embrace micro-frontends and deal with the complexity they introduce. Neither choice is wrong, but they lead to very different futures.

If your application is small and your team fits in one room, stay with the monolith. The coordination overhead is manageable. The tooling is simpler. The learning curve is gentler. Focus on building features and delighting users. Don't solve problems you don't have.

If your application is large and multiple teams are stepping on each other, start planning your migration. The pain you're feeling now will only get worse as you grow. The best time to adopt micro-frontends is before your monolith becomes completely unmaintainable but after you're large enough to benefit from independent deployment.

If you're building something new and expect multiple teams and continuous deployment, design for micro-frontends from the start. The initial setup cost is higher but you avoid the painful migration later. You also avoid accumulating technical debt in a monolith that you'll eventually need to pay down.

The micro-frontend revolution isn't hype. It's a proven architectural pattern solving real problems at scale. Companies like Spotify, IKEA, and Zalando wouldn't invest years migrating to this architecture if it didn't deliver substantial benefits. But it's also not appropriate for every application. Understanding where your application sits on the complexity spectrum determines whether this investment makes sense.

The monolithic SPA era isn't completely over. Small, focused applications will continue thriving with traditional architectures. But for large, complex applications with multiple teams, the writing is on the wall. Micro-frontends are the only proven way to maintain developer velocity and deployment frequency as applications grow. The question isn't whether to adopt micro-frontends eventually, but whether now is the right time for your specific situation.

Choose wisely. The architecture you build today determines how fast you can ship features next year and how many developers you can effectively coordinate. If you choose micro-frontends, commit fully and invest in doing it right. Half-measures will give you all the complexity with none of the benefits. But if you commit and execute well, you'll wonder how you ever lived with a monolithic frontend.